Starkville Public Schools

Segregation, Desegregation, & Integration

Contents: Segregated Education | Fighting Desegregation | Backlash

Segregated Education

By the mid-twentieth century, segregated public education was a cornerstone of the South’s Jim Crow system. The U.S. Supreme Court had sanctioned such practices in the 1899 Cumming v. Richmond County Board of Education case, which gave states the right to determine both who would be educated in taxpayer public schools and exactly what constituted a “separate but equal” education. In the years following, says historian Charles Bolton, “separate but equal education quickly became a fiction” in Mississippi, and African Americans could do little to oppose these developments because they were being simultaneously disenfranchised (Bolton, The Hardest Deal of All , 13).

In Starkville, the city’s dual public education system evolved gradually, mostly during the early twentieth century. By 1918, a small wooden structure, the city’s Rosenwald School stood near the site of the current Henderson complex; it educated African American students up to the tenth grade. In answer to calls for more educational facilities for African American students, the city of Starkville began building a new, wooden structure on the site in 1926-27, funded primarily by the city of itself with contributions from the Rosenwald Fund and local African Americans. It opened as the Oktibbeha County Training School (OCTS) in the late 1920s.

For Starkville’s African Americans, OCTS represented an improvement by offering them access to secondary education within this dual system. Yet the name carried a stigma. As scholar John A. Peoples said, “In many areas of Mississippi, high schools for blacks were called ‘training schools.’ This was based upon the racist assumption that blacks could not be truly educated, but could only be trained like animals” (Schwartz, American Students Organize, 422).

During the late 1950s, in an effort to preserve the city’s dual education system in the wake of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, Starkville officials launched various improvement efforts to make the city’s African American schools appear more equal. They hired new teachers, started new curricular programs (such as French), and constructed new school buildings, including two elementary schools and a new high school. They also renamed Oktibbeha County Training School to Henderson High School, after W. C. (Willie Chiles) Henderson, an African American educator in Starkville in the 1910s who served as principal of OCTS/Henderson High from 1959 until 1964. The goal of the renaming, according to Starkville native Dr. Shirley Hanshaw, was to “discourage our going to white schools.” Although Henderson High was never equal to Starkville High, former teachers and students have fond memories of it. They recall its dedicated administrators and teachers and its successful sports teams and band.

In 1970, under the directive of the courts, Starkville finally ended the long practice of racially segregated education. Students from Henderson High School were transferred to Starkville High School, and the building of Henderson High was demoted to Henderson Middle School, housing ninth grade students. That same year, at a time when tensions over school desegregation were running high in the city, the old Rosenwald School on the site burned to the ground.

Fighting Desegregation

In the momentous Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that segregated public education violated the Fourteenth Amendment. Separate educational facilities, the decision stated, meant unequal facilities for African American students. Another ruling the next year (Brown II) called for desegregation to occur “with all deliberate speed” across the nation.

White residents of Starkville, like other towns across the South, resisted this decision, seeing it as an attack on their way of life. Under additional pressure from the federal government following the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, Starkville and other Mississippi school systems adopted a new freedom-of-choice plan in 1965, which allowed parents to select their children’s school.

As historian Charles Bolton notes, freedom-of-choice “placed excessive burdens on black parents and children to dismantle a dual school system that whites seemingly had no real intention of relinquishing” (Bolton, The Hardest Deal of All, 164). In Starkville as elsewhere, change was negligible; during the five years it existed, few African Americans attended white schools and no whites enrolled at African American schools.

U.S. Department of Education officials and local African American leaders were not satisfied with this plan; they saw it as another attempt to delay desegregation. Attempting to speed up the process, Department of Education officials visited Starkville, threatened loss of funding, and then suspended federal funding in September of 1968. However, the dual system continued.

In 1968, a small group of African American leaders led by Dr. Douglas Conner expressed concern that freedom-of-choice would close black schools and lay off black teachers because whites would not attend African American schools and African Americans would only opt into white schools to desegregate them. Like the Department of Education, they called for the immediate and total desegregation of all grades, while trying to force change through the courts at the same time.

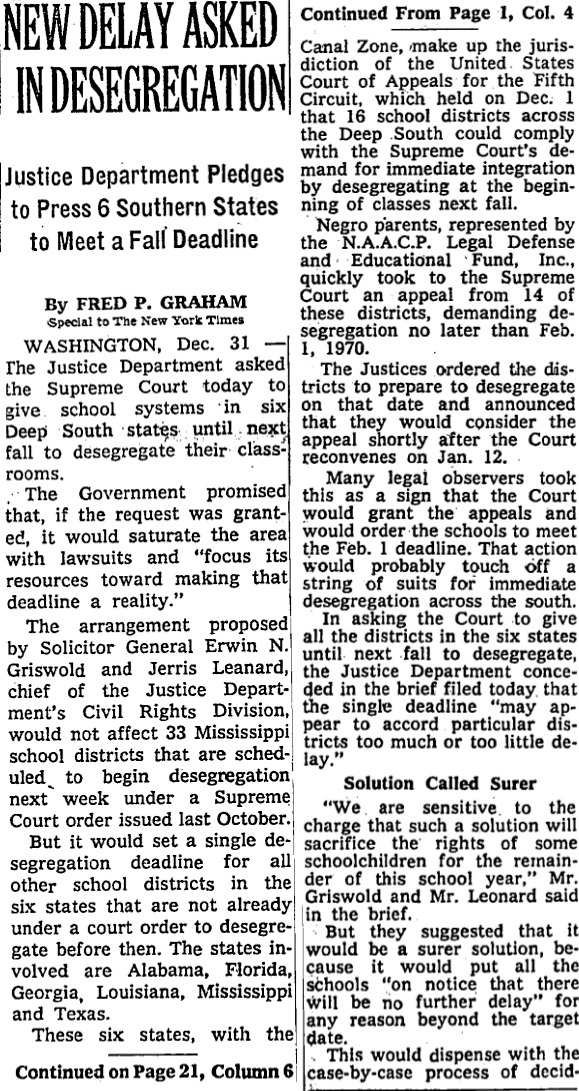

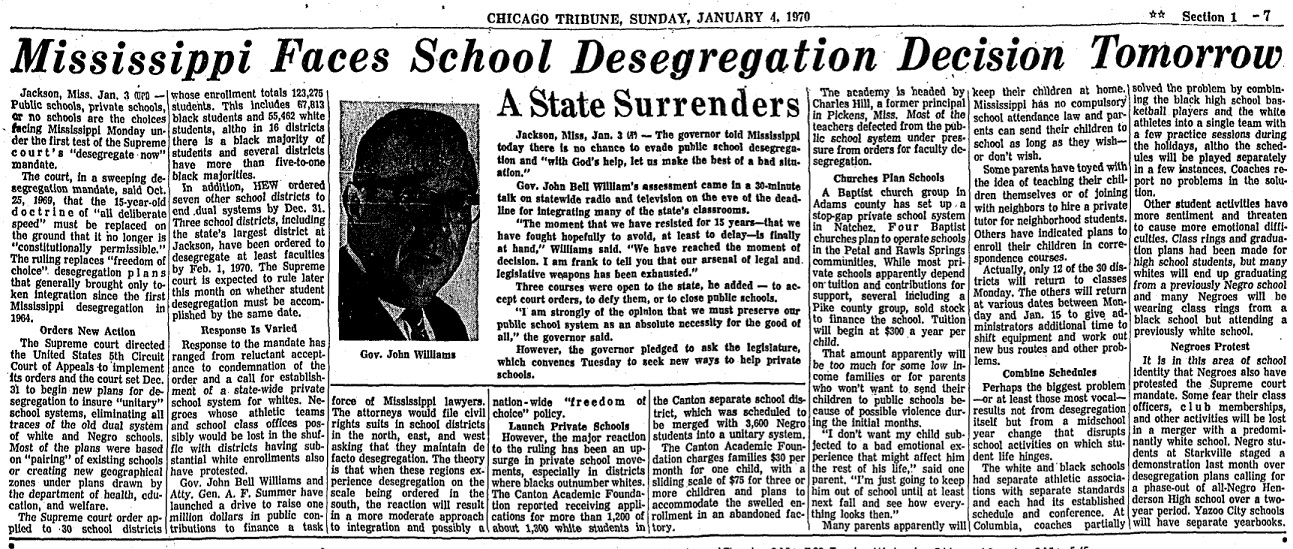

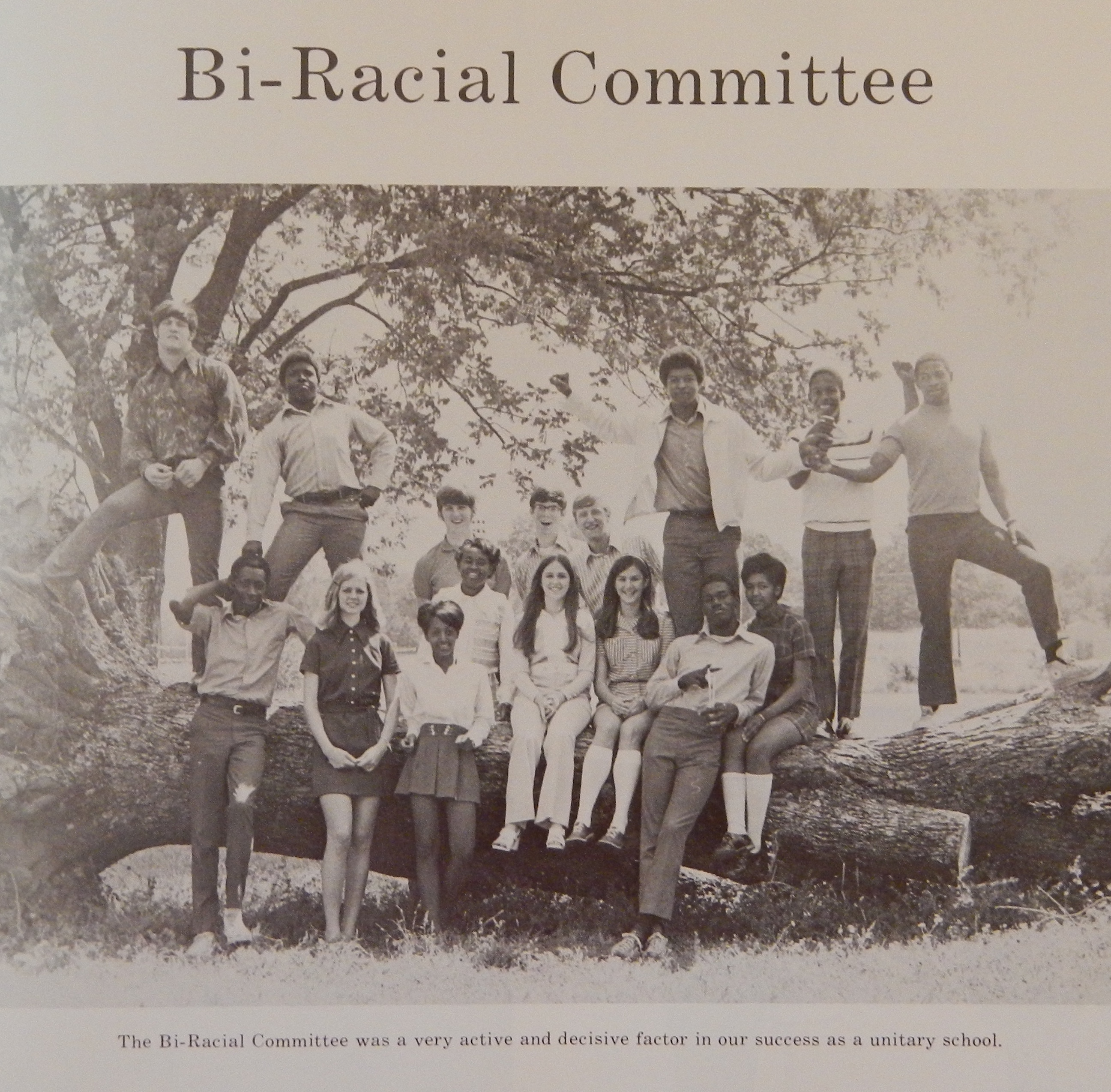

Tensions came to head in 1969 and 1970. At the national level, in the October 1969 Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education decision, the Supreme Court called for the immediate end to segregated school systems in Mississippi, overturning the Brown II doctrine of “all deliberate speed.” A few months later, in February 1970, local legal efforts paid off when a U.S. District Court judge in Aberdeen ordered the end to Starkville’s dual system beginning in the 1970-71 school year. Addressing the fears of the African American community, under this ruling no Starkville school buildings would be closed and school faculty would be integrated. Additionally, a biracial committee would help oversee the process.

Starkville’s segregated public school system finally came to its official end in 1970-1971. As Dr. Douglas Conner noted in his autobiography, “the dual system was eliminated; sixteen years after the Supreme Court ruled segregated schools unconstitutional, Starkville was finally in compliance. It had been a long fight, but it was worth it” (Conner and Marszalek, A Black Physician’s Story, 154).

Yet as evidence in this project attests, 1970-71 was not so much an end as the beginning of a gradual and often tension-filled process that would continue for years to come.

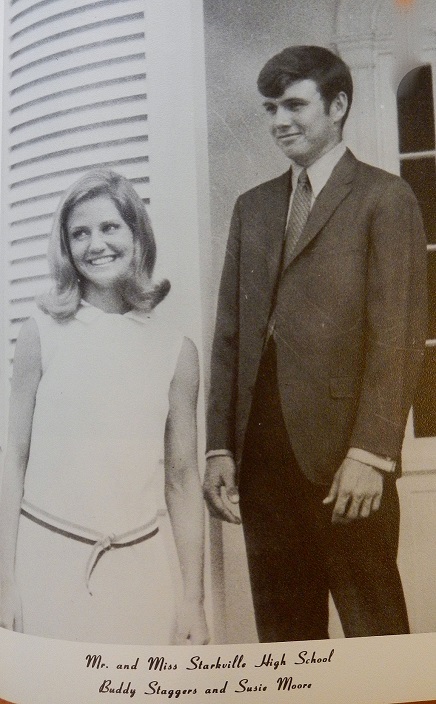

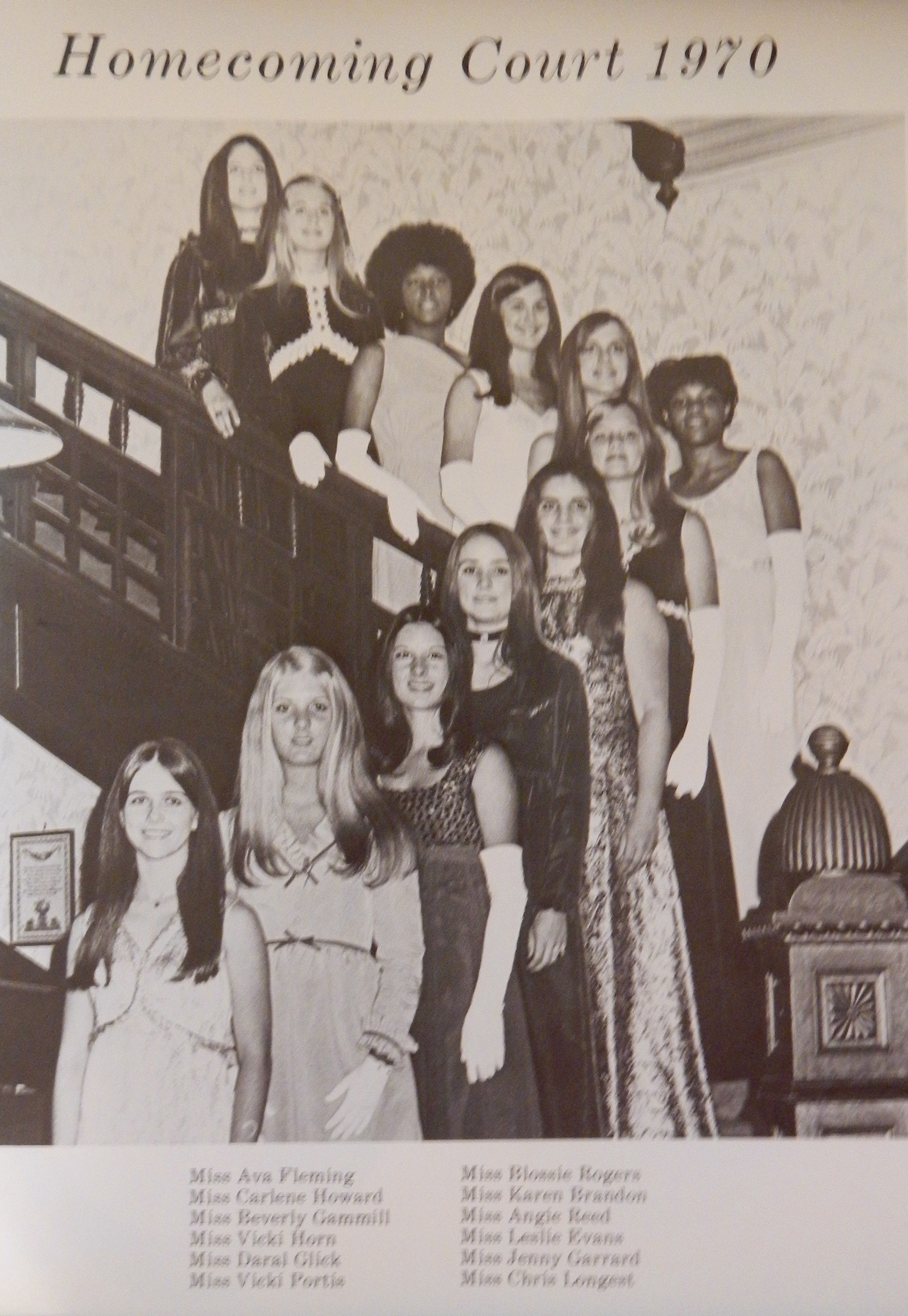

Integration: 1970, year 1

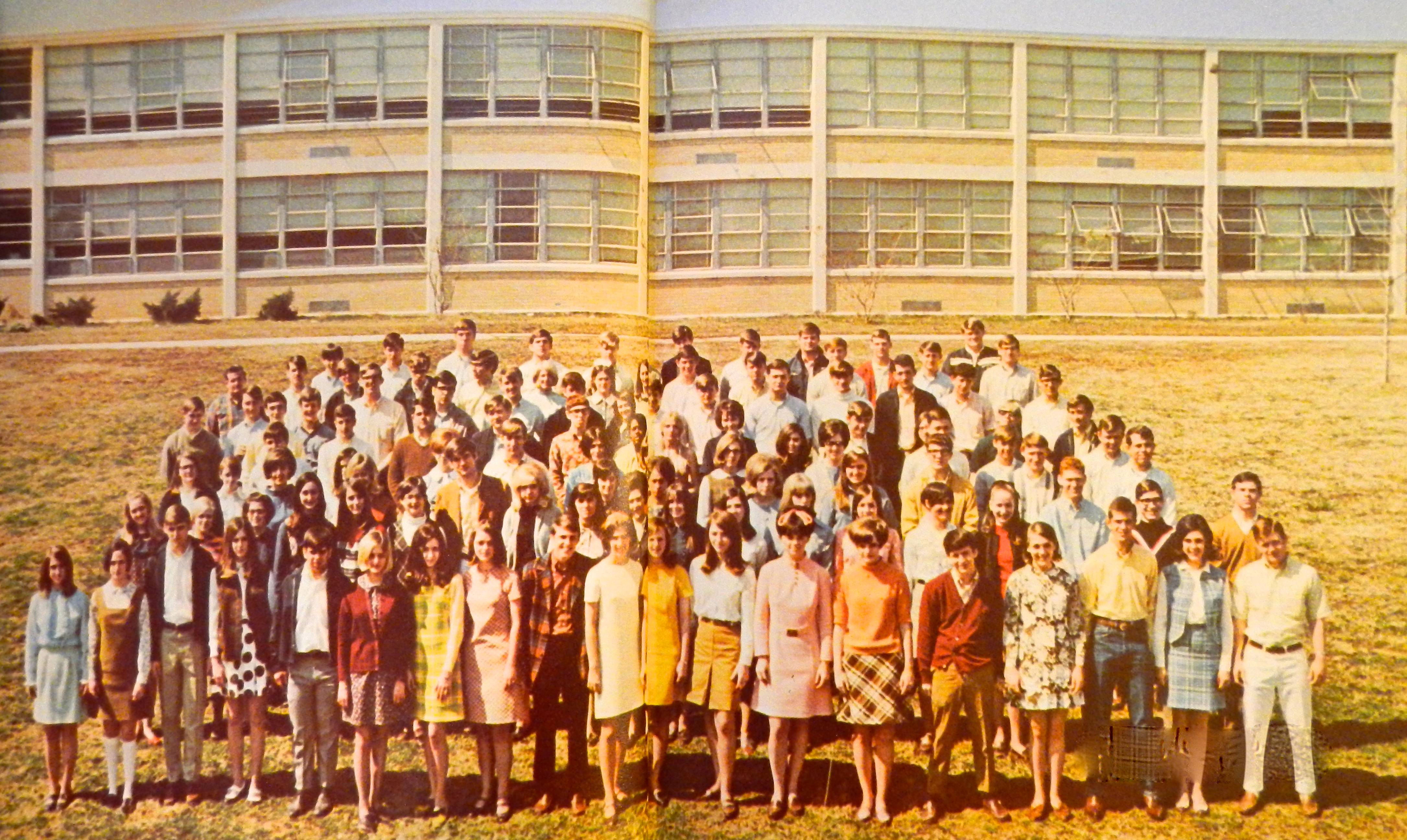

Under the mandate of a court order, Starkville desegregated its public schools during the 1970-71 school year. Desegregation came with costs and opportunities. Henderson High School, the city’s sole African American secondary school, was not closed, as some had feared, but it was downgraded to a middle school, a move that upset many in the community. African American students thus found themselves integrated into the formerly all-white Starkville High. This was a peaceful process, but there was plenty of tension and uneasiness, especially that first year.

That did not hold true for long, as administrators quickly began using standardized achievement test scores to sort students, which effectively re-segregated the school. In 1971, Rosa Stewart, a respected African American teacher, critiqued such “tracking,” noting that there were “‘many all-black classrooms’ taught by black teachers.” (Piper, The Civil Rights Movement in Starkville, MS, 52).

Integration experiences

Backlash

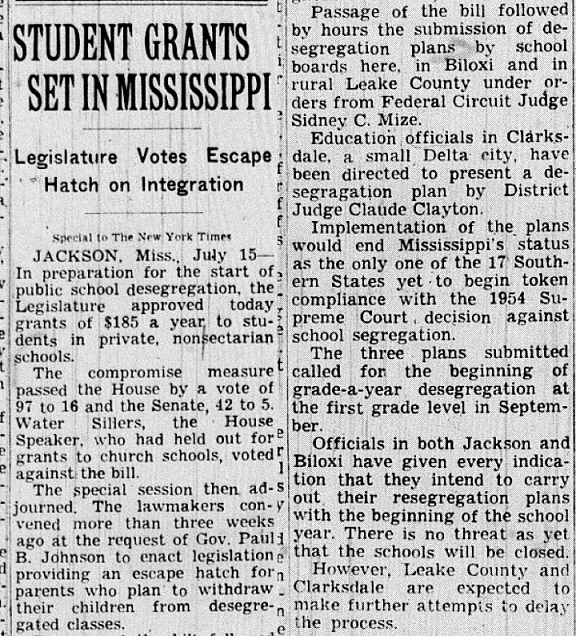

In a state where the children of white elites had long been privately educated and no real public system of education had existed before 1870, taxpayer-supported schools, especially for African American children, were controversial. Reacting negatively to the Brown v. Board of Education decision of 1954, Mississippi legislators proposed a constitutional amendment abolishing the state’s public school system. Its goal was to circumvent school desegregation by transitioning the state’s white students into state supported private schools. Although the amendment failed, it was not the last time Mississippi officials resisted integration by trying to establish private schools.

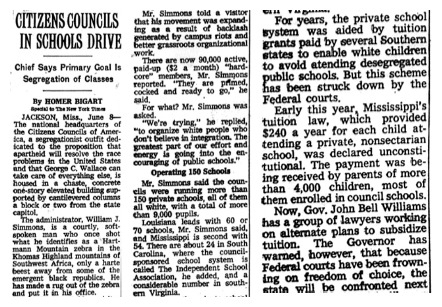

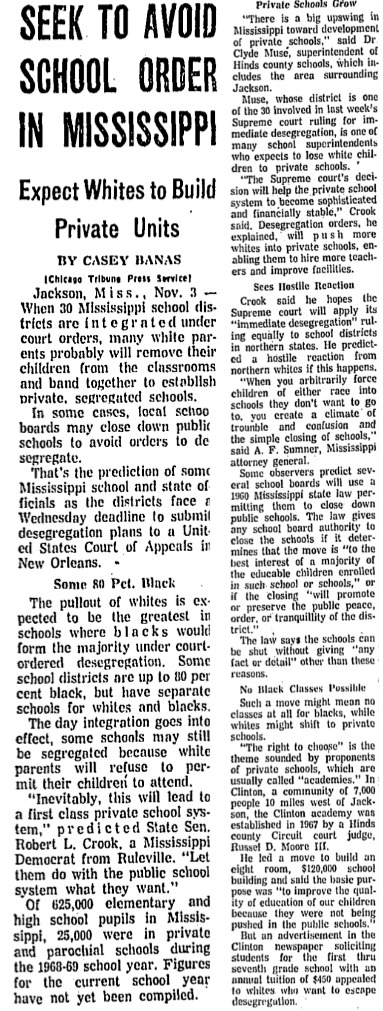

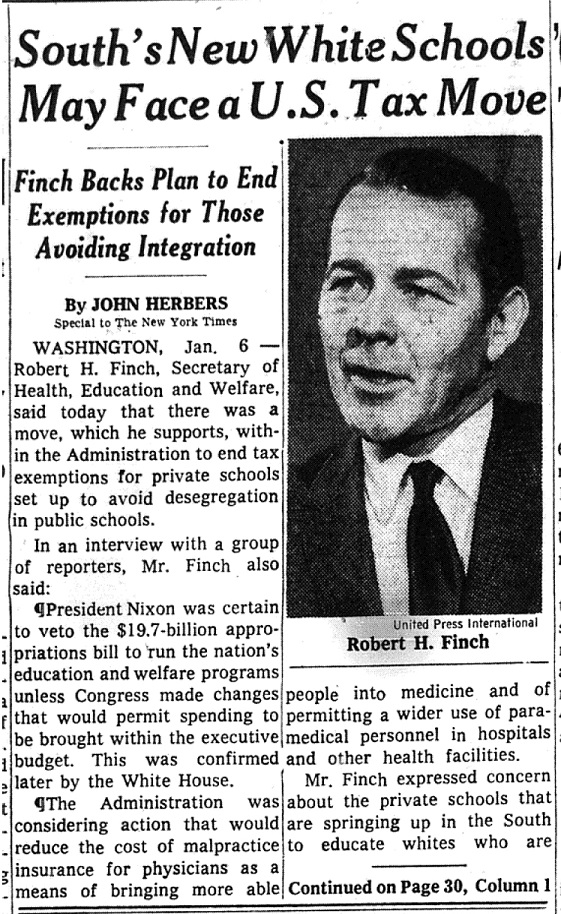

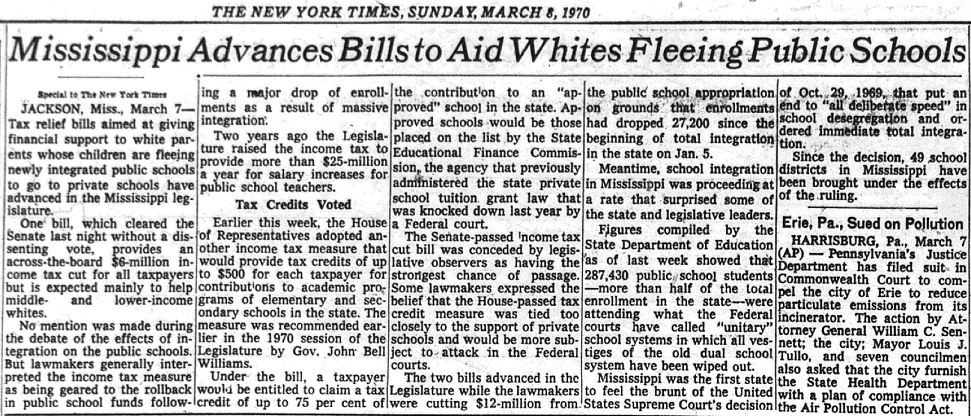

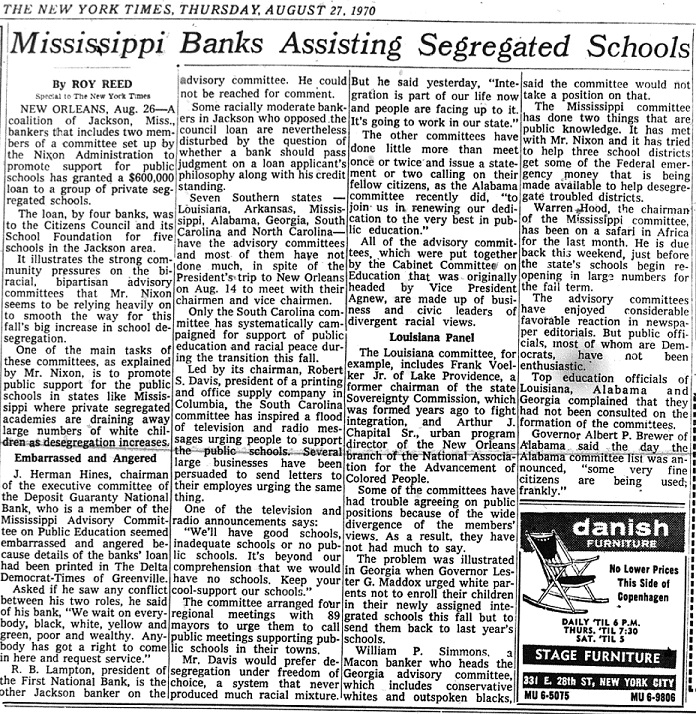

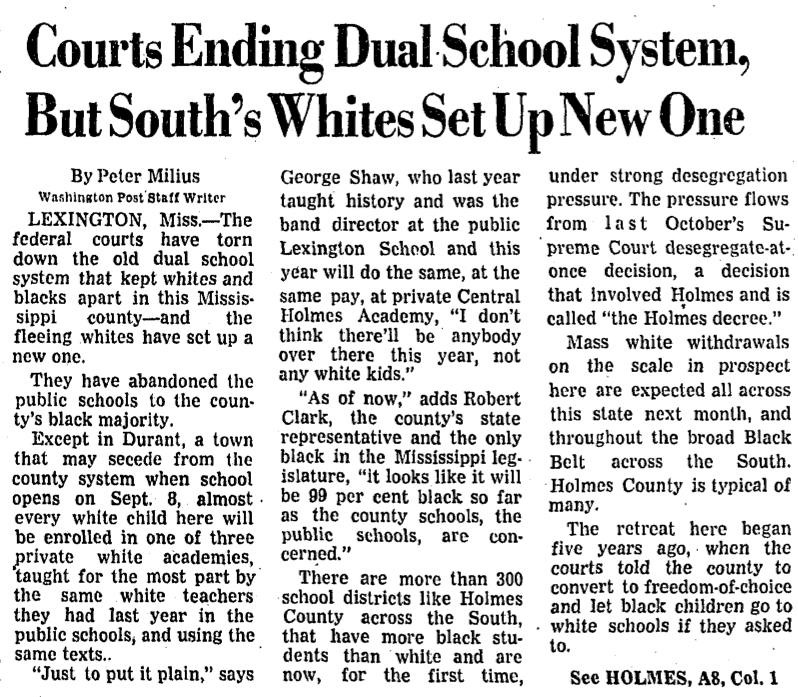

Private school founding exploded in Mississippi between 1964 and 1971 in reaction to increased civil rights activism and the landmark 1969 Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education decision, in which the Supreme Court mandated the immediate desegregation of Mississippi’s public schools. White parents and concerned politicians were outraged by the ruling, arguing that forced desegregation would result in “overcrowded classrooms, poor quality of instruction, breakdown of communication, and busing of children over long distances” (Bureau of Education, 1). By the Spring of 1971 there were 31,950 students enrolled in 106 private segregated schools across Mississippi (Sansing, A Descriptive Survey).

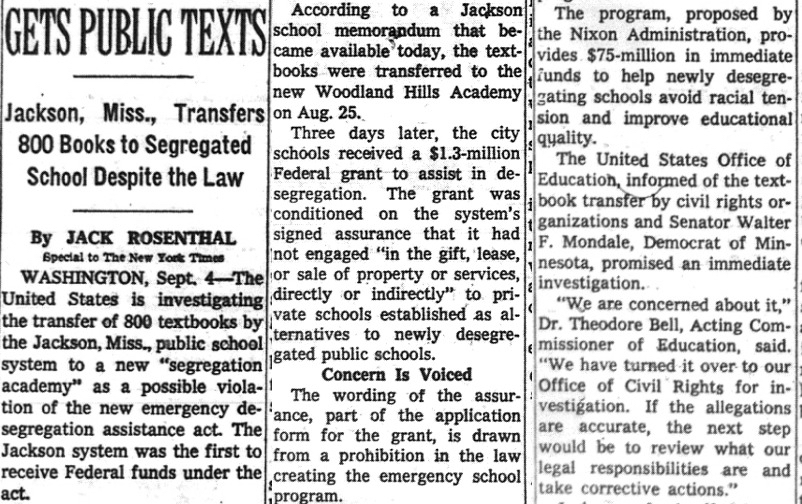

Founded in 1969, Starkville Academy was one of the 115 new private schools established across the state between 1966 and 1970 to resist federally mandated school desegregation (Bolton, The Hardest Deal of All, 173). According to scholar Michael W. Fuquay, “the private school movement was a direct outgrowth of, and in many respects indistinguishable from, the segregationist movement of the White Citizens’ Councils” (Fuquay, “Civil Rights and the Private School Movement,” 160). Oktibbeha County residents were no exception. As local Horace Harned, a former state legislator and State Sovereignty Commission member said in an interview in 1976, “We felt that this would destroy the effectiveness of our public schools and that we must act to oppose and, if possible, reverse this unconstitutional decision to preserve our sovereignty. Thus followed the movement to private schools in the South and the formation of the State Sovereignty Commission by the legislature” (Harned interview, 2).

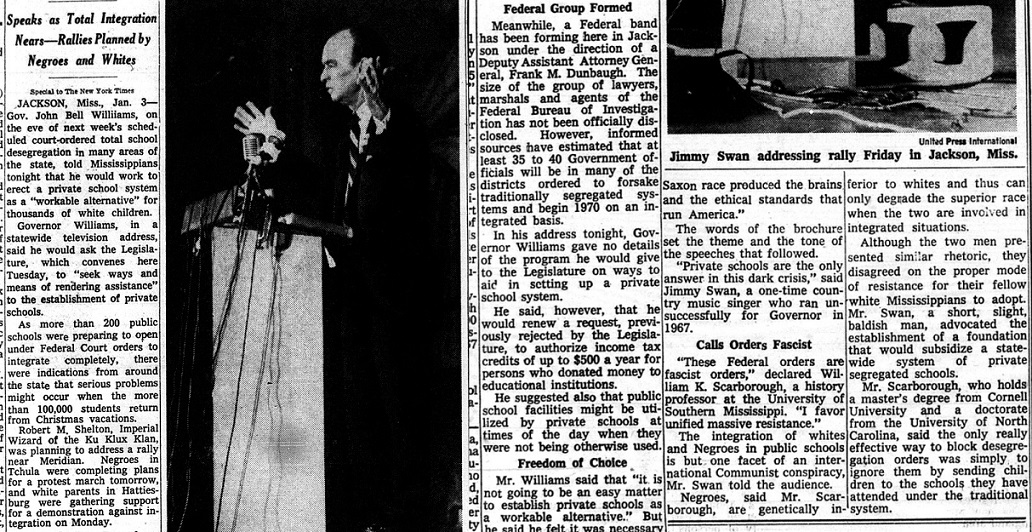

Mississippi’s Governor John Bell Williams sanctioned the push for private, all-white academies, saying that he would “seek ways and means of rendering assistance to the establishment of private schools” and provided state tuition assistance, tax credits, and textbook funding (NYT, 1970).

The founding of private schools perpetuated segregation. In a 1970 interview with the New York Times, an anonymous Mississippi legislator said, “What we’re going to wind up with eventually, is a private school for the white kids and a state-subsidized system for the n—–s” (NYT, Wooten, 1970).

Significantly, not all whites in Starkville supported abandoning the public schools in favor of Starkville Academy; some strongly supported public education. Led by Dr. Charles Lowery, a history professor at Mississippi State University, and his wife, Susie, they urged their white Starkville neighbors to keep sending their children to the city’s public schools, even circulating a petition.