MSU Story

Game of Change, Integration, Campus Activism

Contents: The MSU Story | Game of Change | Richard Holmes Integrates MSU | Charles Evers and Stokely Carmichael

The MSU Story

Mississippi State University (MSU) takes great pride that its integration occurred more smoothly and peacefully than at other Mississippi campuses. There were no riots at MSU; nor were they any major acts of physical violence. But there was lots of tension, and some backlash. For instance, in the 1963 “Game of Change,” no violent incidents occurred, but the team left under cover of night, and following the event, President Colvard received letters filled with vitriol. Likewise, when Richard Holmes first registered for classes at MSU in July 1965, no one hurt him or prevented his registration, but he had to live in isolation and get escorted home. Furthermore, when MSU student groups wanted to invite speakers such as Charles Evers to campus, restrictions prevented these visitors from speaking on campus. While these are not literal acts of violence, these stories demonstrate the kind of obstacles that had to be overcome to bring integration and equal rights to MSU’s campus.

The Game of Change

On March 15, 1963, the Mississippi State University men’s basketball team traveled to East Lansing, Michigan to play Loyola University of Chicago in the NCAA regional tournament semi-final. This was no ordinary game, however, because the Loyola Ramblers started four African American players, and in segregated Mississippi, an “unwritten law” barred the state universities from playing integrated teams.

The lead-up to the game was tense. Five months earlier, James Meredith integrated the University of Mississippi, causing the famous riots that resulted in two deaths and hundreds of injuries. On March 2, Mississippi State University President Dean Colvard announced his intent to send the basketball team to the tournament, claiming the support of the University’s Athletic Committee, student senate, and various alumni chapters.

Before and after Colvard’s decision, everyone from concerned citizens to elected officials voiced their opinion through phone calls and letters to the University. Many supported playing the game; others did not, however, and some of the letters from the opposition were venomous.

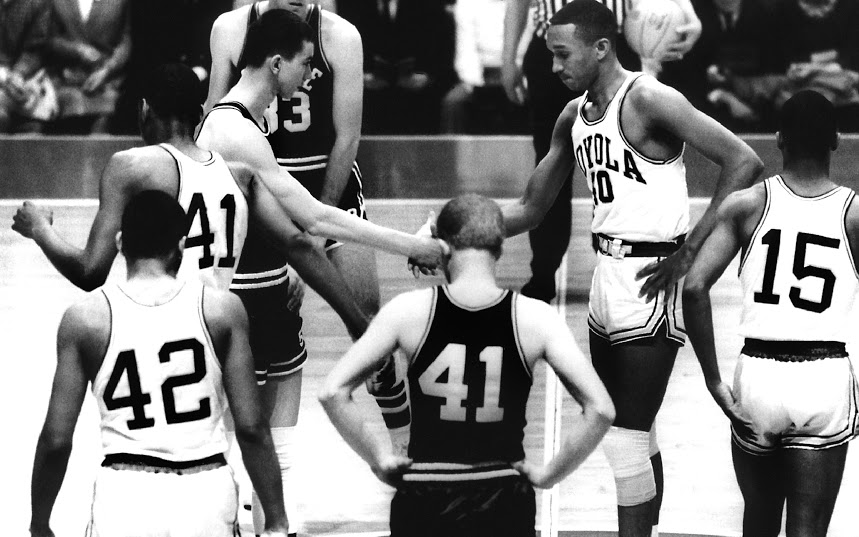

To protect the players from possible violent resistance, the MSU team departed Starkville in secret. No violence occurred the March evening of the “Game of Change,” although not everyone supported the famed handshake between team captains Jerry Harkness (Loyola) and Joe Dan Gold (Mississippi State).

Most scholars argue that the “Game of Change” helped to pave the way the desegregation of MSU’s student body.

While the “Game of Change” was the first sporting event in MSU’s history to push back against the racial status quo, it was not the only one. Through time and under pressure to change, MSU gradually integrated its other sports and coaching staffs.

Minutes and Press Releases on the game

From the Mixed Emotions Collection, Dean W. Colvard Faculty Papers, Special Collections, University Archives, Mississippi State University Libraries.

Letters about the Game

Letter of Support

Letter of Disapproval

Richard Holmes Integrates MSU

In July 1965, Richard Holmes quietly desegregated Mississippi State University as its first African American student. He entered MSU during the summer semester, after attending Wiley College in Marshall, TX for two years. Holmes, the adopted son of local civil rights leader, Dr. Douglas Conner, was born in Chicago, IL on February 17, 1944, and moved to Starkville when he was 12 years old. He graduated from Starkville’s segregated Henderson High School in 1963.

Holmes’s admission to MSU met with relatively little resistance from the local community, at least in comparison to the violent repercussions that James Meredith faced at the University of Mississippi or the vicious backlash Clyde Kennard experienced the University of Southern Mississippi. The local Sheriff’s department worked diligently to keep the Klan out of Oktibbeha County and guarantee Holmes’s safety. In his interview he said, “I feel that Mississippi State University was a different university . . . the community was different, … the … university was different, and the administration was different.”

His first year at MSU was not an easy transition. He said, “It was isolated, it was lonely at times . . . it was somewhat depressing at times . . .” Most students on campus chose to ignore his presence, but he did find support among faculty and a few students. He said, “Professors in History were my biggest supporters.” He graduated in 1969 with a bachelor of art while teaching at a high school in Aliceville, Alabama. He earned a medical degree from Michigan State University in 1973.

Although Holmes was MSU’s first African American student, he was not the first local student urged to enroll. Dr. Conner had asked Shirley Hanshaw’s parents if she would be the one to desegregate MSU. Hanshaw, another Henderson High graduate and a National Achievement Scholar, seemed an obvious choice. Her parents declined his offer, however, fearing that their introverted daughter would be crushed by the experience. Hanshaw opted to attend Tougaloo College instead.

Charles Evers and Stokely Carmichael

In the early 1970s, notable Civil Rights activists visited the MSU campus and spoke to students about national struggles. Their approaches reflect the changing nature of the Civil Rights Movement.

One visitor was Charles Evers, older brother of Medgar Evers and then mayor of Fayette, MS. Initially Charles was banned from speaking at MSU until the Fifth United States Circuit Court of Appeals declared that the banning of speakers at state institutions was unconstitutional (“Evers Visits Campus,” The Reflector, March 10, 1970). After this ruling, he was asked to speak at Mississippi State University by the Young Democrats on March 9, 1970. In his speech, Evers advocated for the employment of more black faculty members and improved race relations throughout the state. Evers also touched on unresolved issues – taxes, public education, social programs – that the state of Mississippi faced at the time.

In 1973, the Afro-American Plus Club invited Stokely Carmichael to speak at Mississippi State University. One of the club’s core values were to “instill Black pride, educate all about Black culture, and promote peaceful coexistence with other student” (Afro-American Plus Club Constitution, Article II, from “Black Awareness Month” Vertical File, Special Collections, University Archives, Mississippi State University Libraries). To the students of the Plus Club, the organization’s beliefs were parallel to Stokely Carmichael’s concept of Black Power. It can be argued that the state of Mississippi is the home to the Black Power Movement. During the March Against Fear in 1966, Stokely Carmichael was arrested in the Greenwood, Mississippi where in his frustration with racism he yelled the phrase “Black Power.” See Austin’s Up Against the Wall and Ogbar’s Black Power.

In 1973, Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture) returned the state of Mississippi on October 30th where he spoke at MSU on the topics of “Pan-Africanism and Socialism.” His philosophy represents a shift from the traditional thought of the older vanguard — such as the “unity” approach presented by Charles Evers — to what was perceived by some as dangerous and selfish.

Student Activism and Responses

In the early 1970s, student organizations such as the YMCA and the Afro-American Plus Club attempted to create opportunities for African American students to be more involved in academic and campus life. As previously mentioned, they hosted notable speakers, but they also programmed cultural and intellectual events to discuss topics that were important to African American students. For example, they held exhibits on African art during “Black History Week” (before February was designated as Black History Month), and forums to discuss inclusion in campus organizations.

In spite of their small-but-growing presence on campus since Richard Holmes’ integration in 1965, African American students faced opposition to many of their requests, both from individuals, and often from the campus organization, such as the Student Association. For example, in addition to the speaker ban on campus, students reported feeling excluded from certain places on campus, like the Student Union. Even though African Americans reached a milestone through integrating the university the previous decade, they still reported feelings of exclusion and experienced discrimination.