Getting Organized

Organization efforts, NAACP, and Boycotts & Protests

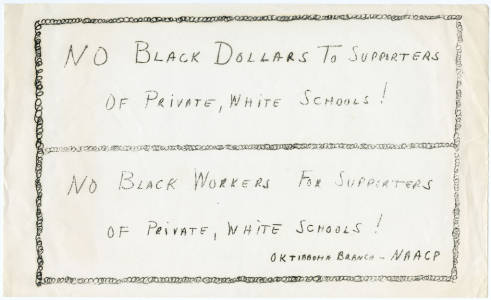

Image: “Anti-integration cartoon,” Segregation-Integration Misc. Collection, Manuscript Collections, Mississippi State University Libraries.

Contents: Getting Organized | Oktibbeha County NAACP | Boycotts and Protests

Getting Organized

Unlike other regions of Mississippi in the early 1960s, there was no organized resistance to segregation in Starkville, but local citizens sometimes took it upon themselves to push back against the racially divided society. During this time, Jim Crow segregation excluded African Americans from white-owned restaurants, cafes, or anywhere white patrons could sit down. Breaking these rule could mean jail time, but some residents willingly took this risk.

Starkville’s white-owned grocery and clothing stores accepted African Americans as patrons, but according to historian Craig Piper, “they were not allowed to try on merchandise or receive alterations.” (Piper, The Civil Rights Movement in Starkville, MS, 20). In addition, white business owners refused to hire black employees to work in the front of their stores. African Americans resented such lack of visibility and equal employment opportunity, but they did not protest these practices in any organized way until 1970.

“At clothing stores we were discouraged from trying anything on. We were supposed to hold the clothes against our bodies to try to determine correct fit.” (Conner and Marszalek, A Black Physician’s Story, 103) -Douglas Conner

Following passage of the federal Civil Rights and Voting Acts in 1964 and 1965, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, and motivated by ongoing local economic, educational, and political frustrations, Starkville’s African American community followed the lead of others in the state and mobilized more organized forms of resistance by the late 1960s.

In 1969, physician Douglas Conner, a leader within the city’s African American community, founded Oktibbeha County’s first NAACP chapter, which helped solidify resistance. In his speech at the first chapter meeting, Dr. Conner called for local African Americans to unite. He said, “We can speak out, we must speak out–not as lonely voices in the wilderness but as one large, united, dynamic, courageous whole. . . As of this hour, let us resolve that as black Mississippians, we will no longer permit or tolerate injustice.” Dr. Conner urged those in attendance to respond “using whatever legal means that are available or appropriate to the act”

Over time, Starkville’s African Americans did just that, by fighting for rights and equal opportunities in the schools, the courts, and in the streets.

Oktibbeha County NAACP

Sometime during the late 1950s, following a visit to Starkville by NAACP state field secretary, Medgar Evers, local African American leader Dr. Douglas Conner began to consider founding a local chapter in Starkville. Evers told Conner “Starkville needs a chapter of the NAACP” and suggested that Conner would be the right person to lead it (Conner and Marszalek, A Black Physician’s Story, 105). Conner knew well that nearby Columbus had the state’s largest chapter in 1953 with four hundred members, and that their leader, the Columbus dentist, Dr. Emmett J. Stringer had served one term as state president of the NAACP. It seemed logical that Starkville, home to Mississippi State University, should have a chapter as well.

Founding a local chapter happened slowly, however, even though Conner became personally active in the organization. Only during the mid-1960s, as some Starkville African Americans gradually joined Conner and other black leaders in voter registration drives, did locals become more receptive to the idea of it. Support finally coalesced in 1969 when prompted by mounting concerns over the still-segregated public school system and continued unequal employment and shopping opportunities in the downtown.

The Oktibbeha County chapter of the NAACP was founded on April 1, 1969 at Starkville’s Griffin Methodist Church. In his keynote address, Dr. Conner called upon the “foot-draggers in the black community” to act, reminding them that change would happen only by acting “as one, large, united, dynamic, courageous whole” (Conner and Marszalek, 149).

Under Conner’s leadership durings the 1970s and 1980s, the Oktibbeha County NAACP served as a linchpin in the local struggle for social justice. The chapter played a pivotal role in pushing for school desegregation, equal treatment of African American school teachers and administrators, and equal employment and shopping opportunities in the downtown.

Later, under the chapter’s first female president, Dorothy Bishop, the chapter continued to press for equal treatment under the law for local African American citizens in the 1990s.

One of the former presidents of the local chapter is Chris Taylor, who is interviewed on this site.

Watch Chris Taylor’s Interview

Documents on the Oktibbeha NAACP

Courtesy of Mississippi State University Libraries Special Collections

Boycotts and Protests

Economic and employment opportunities for Starkville’s African Americans during the 1960s and 70s differed little from those offered to them during the 1940s or 50s. Just as in the past, white business owners deliberately employed African Americans in subservient positions to preserve Mississippi’s hierarchical society, one structured by race and class. Such hiring practices, as scholars explain, had paradoxical effects. On the one hand, the African American community grudgingly accepted these menial jobs because they meant employment that brought wages to support families. On the other hand, these subservient positions stigmatized African Americans as lesser citizens than their white neighbors.

Employment was not the only issue. Starkville’s African Americans also had to endure marked double-standards when trying to purchase goods, services, or food at downtown businesses and restaurants. They were not allowed to try on clothes in clothing stores or to sit-down and be served at restaurants where whites were present; they also suffered the indignity of having to enter businesses or offices through separate side or back doors.

Starkville was not alone in these practices; during the Jim Crow Era they were common throughout the state of Mississippi. Starkville’s African Americans were fairly late in resisting them, however; for it was not until 1970 that local black citizens reacted to these injustices.

In February 1970, Dr. Douglas Conner formed the Oktibbeha County Black Caucus. The members included: Bennie Butler (a barber); W.B. Robinson (an undertaker); Clarence Taylor (a pool hall owner); John McGhee, (a laborer at the University); and Thomas Brooks, (a carpenter). This group met with white business owners about the absence of African American salespeople, yet these business owners retorted that they could not hire African Americans into more visible jobs as clerks and salespeople because they feared the loss of their “white trade.” Although Conner reminded them that they had many if not more African American patrons, his comments fell on deaf ears. Business owners continued to resist hiring African Americans into public contact positions.

After these discussions failed, Dr. Conner turned to Starkville’s local government. Dr. Conner and the Oktibbeha County Black Caucus asked city officials to “encourage merchants to hire black workers,” but city officials deflected, stating that they could not intervene in private business practices.

After arriving at an impasse, the Oktibbeha County Black Caucus called for a boycott in April of 1970. The members drafted a list “where blacks regularly shopped … and encouraged black citizens to boycott them until black help was hired” (Conner and Marszalek, A Black Physician’s Story, 160). To put his plan into action, Dr. Conner traveled to local churches one Sunday in April to announce the boycotts and passed out leaflets that explained their strategies. Later that day African Americans created picket signs that read “No Black Sales People, No Businesses” and “Black Should Be Treated Fairly (Conner and Marszalek, A Black Physician’s Story, 160).”

As support for the boycotts increased, opposition grew in tandem. Local newspapers ignored the protests. There were internal divisions too; some African Americans believed that the protests were doing more harm than good. By the summer of 1970, city officials threatened to stop issuing permits to protesters; Starkville police also began arresting many protesters. These obstructionist tactics failed miserably, however. Hundreds of protesters went to jail, but once released they returned to the streets to peacefully demand change.

After feeling the effects of the boycott, white business owners requested a meeting with the Oktibbeha County Black Caucus. Still, their refusal to hire African American salespeople did not change. By the fall of 1970, with Christmas approaching and black support for the boycott dwindling, business owners finally seemed ready to compromise, promising to hire some African American salespeople if the boycott ended. Although the promise seemed empty, Dr. Conner called off the boycott in the hopes that the merchants would act on their word. They did, but only in part. Sometime after the boycott, a few downtown businesses hired African American salespeople.

The boycott was thus successful in premise, but for Dr. Conner and the citizens of Starkville it was clear that there was much more to be accomplished.

Tombigbee Council on Human Relations, Box 6, Starkville City Brochures and Maps Folder, Special Collections, Manuscripts, Mississippi State University Libraries.

Technical Credits - CollectionBuilder

This digital collection is built with CollectionBuilder, an open source tool for creating digital collection and exhibit websites that is developed by faculty librarians at the University of Idaho Library following the Lib-STATIC methodology.

This site is built using CollectionBuilder-gh which utilizes the static website generator Jekyll and GitHub Pages to build and host digital collections and exhibits.